Distributed Transactions

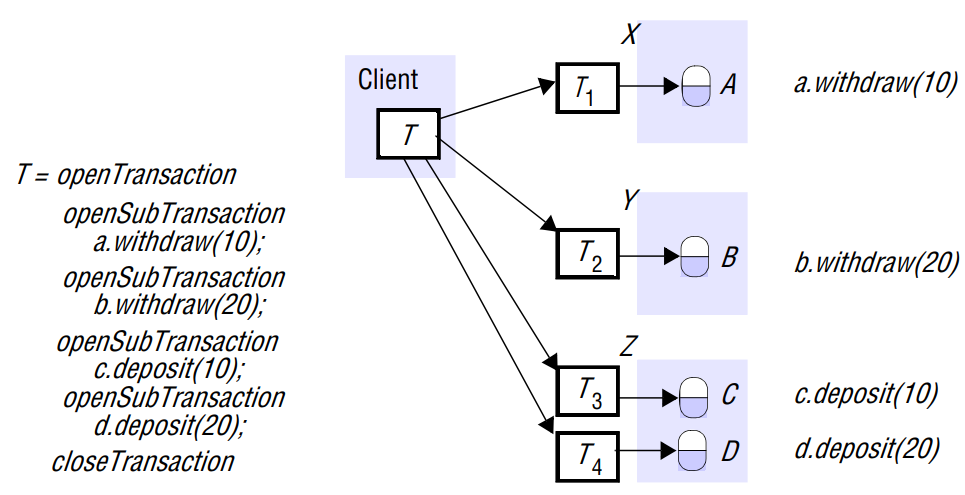

In a distributed DBMS, a transaction usually involves multiple servers. Consider a transaction that a client transfers 10 dollars from account A to C and then transfers 20 dollars from B to D, and each of these accounts is stored in different servers as shown in the graph. If any one server in this transaction fails, the whole transaction needs to abort.

A client transaction becomes distributed if it invokes operations in several different servers. This document talks about the main strategies to achieve ACID properties for distributed transactions.

Two-Phase Commit Protocol

The two-phase commit protocol (2PC) was devised to ensure the atomicity property in a distributed DBMS. where the atomicity property requires that when a distributed transaction comes to an end, either all of its operations are carried out or none of them.

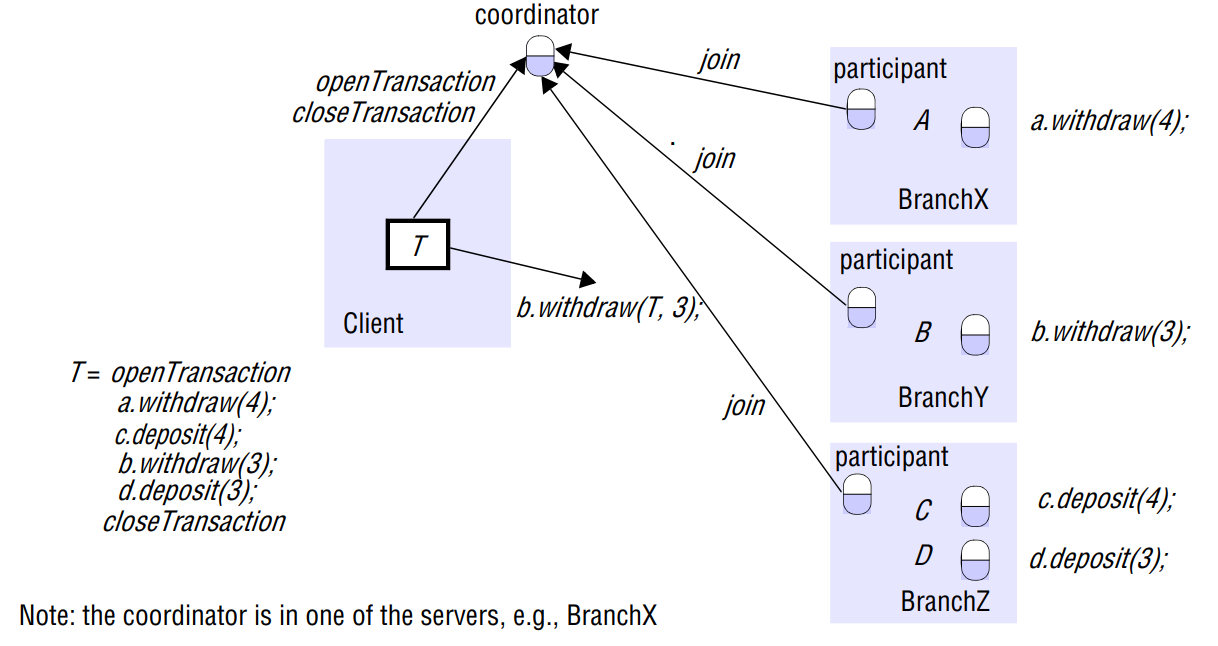

In 2PC, firstly, a server is selected to be the coordinator, which communicates with the client and coordinate the work on all servers.

In the first phase of 2PC, each participant votes for the transaction to be committed or aborted. Once a participant has voted to commit a transaction, it is not allowed to abort it. Therefore, before a participant votes to commit a transaction, it must ensure that it will eventually be able to carry out its part of the commit protocol, even if it fails. A participant to said to be in a prepared state if it votes to commit.

In the second phase of the protocol, the coordinator decides the final decision (either abort or commit), every participant in the transaction carries out the joint decision.

To formally define the protocol, we first list the operations (interfaces) in the protocol:

- canCommit(trans) Yes / No

- Call from coordinator to participant to ask whether it can commit a transaction. Participant replies with its vote.

- *doCommit(trans)

- Call from coordinator to participant to commit its part of a transaction.

- doAbort(trans)

- Call from coordinator to participant to abort its part of a transaction.

- haveCommitted(trans, participant)

- Call from participant to coordinator to confirm that it has committed the transaction.

- Just for deleting stale information on the coordinator.

- getDecision(trans) -> Yes / No

- Call from participant to coordinator to ask for the decision on a transaction after it has voted Yes but has still had no reply after some delay. Used to recover from server crash or delayed messages.

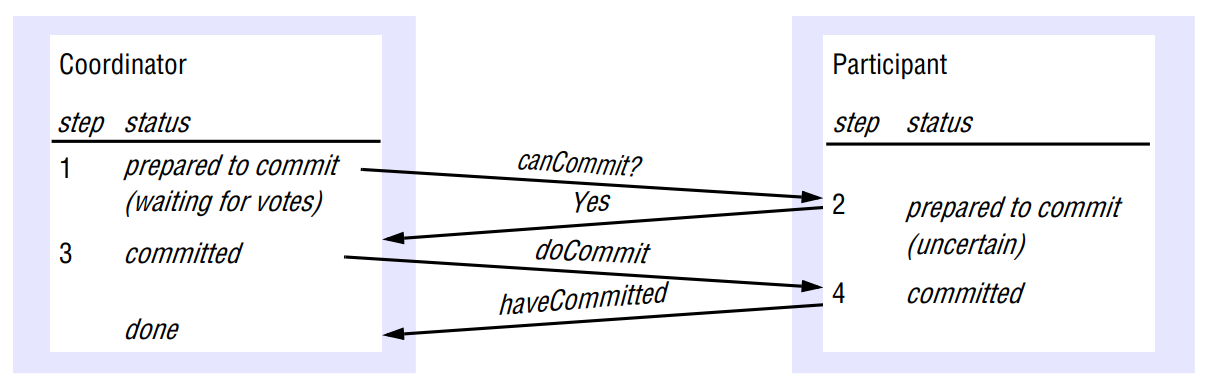

Phase 1

- The coordinator sends a canCommit? request to each of the participants in the transaction.

- When a participant receives a canCommit? request it replies with its vote (Yes or No) to the coordinator. Before voting Yes, it prepares to commit by saving objects in permanent storage. If the vote is No, the participant aborts immediately.

Phase 2

- The coordinator collects the votes (including its own).

- If there are no failures and all the votes are Yes, the coordinator decides to commit the transaction and sends a doCommit request to each of the participants.

- Otherwise, the coordinator decides to abort the transaction and sends doAbort requests to all participants that voted Yes.

- Participants that voted Yes are waiting for a doCommit or doAbort request from the coordinator. When a participant receives one of these messages it acts accordingly and, in the case of commit, makes a haveCommitted call as confirmation to the coordinator.

Timeout is employed in 2PC.

- If a participant votes yes, but not receiving any reply from the coordinator after a certain time, it enters the uncertain state. It can make a getDecision request to the coordinator to determine the outcome.

- Since after a participant votes yes, it can’t do anything until receive a decision from the coordinator. Thus, if a coordinator fails, it must be replaced.

- Conversely, if a participant can’t vote in a certain time, the coordinator must announce doAbort to all participants.

Timestamp Ordering

Similarly, the isolation property needs to be preserved in distributed transactions. There are two meanings behind isolation in distributed DBMSs:

- Each server needs to be responsible for applying concurrency control to its own objects.

- All members of a distributed transactions are jointly responsible for ensuring that they are performed in a serially equivalent manner.

We mainly talk about 2 in this article, where “serially equivalent manner” or “serializability” means if transaction T is before transaction U in their conflicting access to objects at one of the servers, then they must be in that order at all of the servers whose objects are accessed in a conflicting manner by both T and U.

The most common protocol is the timestamp ordering. in the protocol, similarly, a central coordinator is selected.

- The coordinator issues a timestamp – the globally unique transaction timestamps – to each transaction when it starts to participants. All members are responsible for ensuring that transactions execute in the order of timestamp.

- The transaction timestamp is passed to the coordinator at each server whose objects perform an operation in the transaction. In this way, the coordinator can find the potential inconsistency

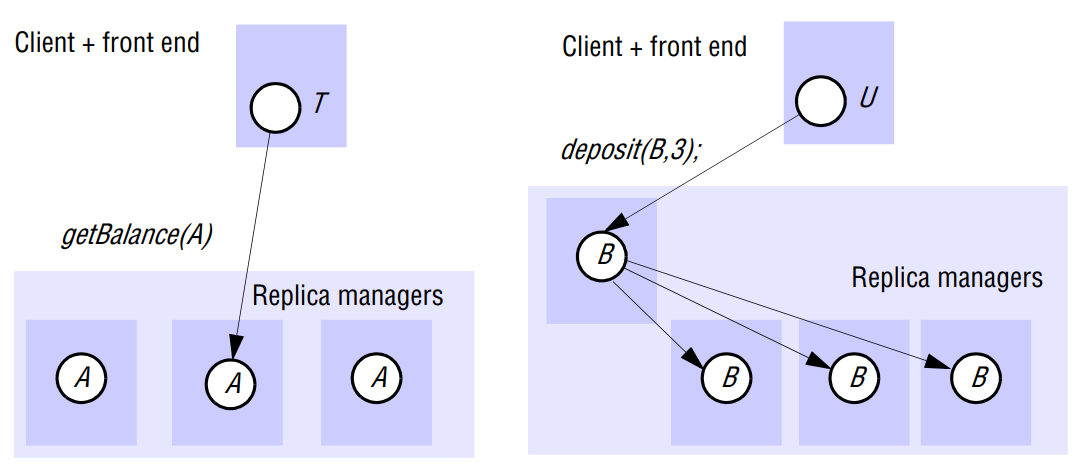

One-copy Serializability

There is a final concerns of distributed transactions. Usually, for increasing data availability, there are replicas for objects. From a client’s viewpoint, a transaction on replicated objects should appear the same as one with non-replicated objects. This property is named one-copy serializability. It is similar to, but not to be confused with, sequential consistency or sequential serializability.

The simplest protocol to achieve one-copy serializability is read-one/write-all. As its name suggests, when it reads, it can read from any one of the replicas. But a write requests must be performed on all replicas by the replica manager.

Simple read-one/write-all replication is not a realistic scheme, because it cannot be carried out if some of the replica managers are unavailable. This deficiency essentially contradicts with the purpose of replicas because replicas scheme is designed to allow for some replica managers being temporarily unavailable.

A more realistic protocol is local validation. It allows a transaction to write only to available replicas. However, before a transaction commits it checks for any failures (and recoveries) of replica managers of objects it has accessed. A transaction can only commits if there is no failure and recovery of replicas which stores the object used in the transaction.

Reference

Coulouris, George F., Jean Dollimore, and Tim Kindberg. Distributed systems: concepts and design. pearson education, 2005.