Transaction Management

The document summarize transaction management in database.

Content from Unimelb Master Subject COMP90050

Background

Some cliché here: Transaction is a unit of work in a database Properties of transaction: ACID

- Atomicity. Either all operations of the transaction are reflected properly in the database, or none are

- Consistency. Execution of a transaction in isolation (i.e., with no other transaction executing concurrently) preserves the consistency of the database.

- What is “consistent” often depends on applications

- Not easily computable in general

- Isolation. Even though multiple transactions may execute concurrently, the system guarantees that, for every pair of transactions, it appears that one is unaware of another

- mainly about concurrency control

- Durability. After a transaction completes successfully, the changes it has made to the database persist, even if there are system failures.

Not all operations can have ACID. Three types of operations in DBMS

- Unprotected actions. actions with no ACID. e.g. low level read and write from memory / disk

- Protected actions

- Real actions. These actions affect the real, physical world in a way that is hard or impossible to reverse. theoretically impossible to implement ACID. e.g. printing a report, sending a SMS message…

Transaction from Programmers Perspective

Not all queries can be expressed in SQL, so a transaction often works with a general purpose language such as C and Java

Two approaches to accessing SQL: Dynamic SQL and Embedded SQL

- Dynamic SQL ← construct and submit SQL queries at runtime. e.g. JDBC

- Embedded SQL ← compile SQL statement at compile time. e.g. C Embedded SQL

The main distinction between Dynamic SQL and Embedded SQL is the existence of Pre-processing. Preprocessing can catch errors in the compile stage e.g. type error, SQL syntax error, but it complicates debugging of the program and even causes ambiguity because it, actually creates a new host language. As a result, most modern systems use dynamic SQL.

Finally, note that nondeclarative actions in programs – printing to terminal, sending result to UI – cannot be undone by DB

C Embedded SQL

Example a flat transaction.

First, create a function with no transaction

int main() {

exec sql BEGIN DECLARE SECTION;

/* The following variables are used for communicating between SQL and C */

int OrderID; /* Employee ID (from user) */

int CustID; /* Retrieved customer ID */

char SalesPerson[10] /* Retrieved salesperson name */

char Status[6] /* Retrieved order status */

exec sql END DECLARE SECTION;

/* Set up error processing */

exec sql WHENEVER SQLERROR GOTO query_error;

exec sql WHENEVER NOTFOUND GOTO bad_number;

/* Prompt the user for order number */

printf ("Enter order number: ");

scanf_s("%d", &OrderID);

/* Execute the SQL query, simple query no transaction definition */

exec sql SELECT CustID, SalesPerson, Status

FROM Orders

WHERE OrderID = :OrderID;// ”:” indicates to refer to C variable

INTO :CustID, :SalesPerson, :Status;

printf ("Customer number: %d\n", CustID);

printf ("Salesperson: %s\n", SalesPerson);

printf ("Status: %s\n", Status);

exit();

query_error:

printf ("SQL error: %ld\n", sqlca->sqlcode); exit();

bad_number:

printf ("Invalid order number.\n"); exit();

}

Then, put transaction into the example: Everything between

exec sql BEGIN WORK;

and

exec sql COMMIT WORK;

is seen as transaction.

e.g.

DCApplication() {

exec sql BEGIN WORK;

AccBalance = DodebitCredit(BranchId, TellerId, AccId, delta);

// Consistency Check

if (AccBalance < 0 && delta < 0) {

// Inconsistent

// Let dbms undo whatever it has done

exec sql ROLLBACK WORK;

} else {

send output msg;

exec sql COMMIT WORK;

}

}

Long DoDebitCredit(long BranchId, long TellerId, long AccId, long delta) {

exec sql UPDATE accounts

SET AccBalance =AccBalance + :delta

WHERE AccId = :AccId;

exec sql SELECT AccBalance INTO :AccBalance

FROM accounts WHERE AccId = :AccId;

exec sql UPDATE tellers

SET TellerBalance = TellerBalance + :delta

WHERE TellerId = :TellerId;

exec sql UPDATE branches

SET BranchBalance = BranchBalance + :delta

WHERE BranchId = :BranchId;

Exec sql INSERT INTO history(TellerId, BranchId, AccId, delta, time)

VALUES( :TellerId, :BranchId, :AccId, :delta, CURRENT);

return(AccBalance);

}

the transaction will either survive together with everything from BEGIN WORK to COMMIT WORD, or it will be rolled back with everything (abort).

Dynamic SQL

Take JDBC as an example.

Mainly four steps:

- Open a connection

- Create a statement object

- Execute queries using the statement object to send queries and fetch results

- Exception mechanism to handle errors

public static void JDBCexample(String userid, String passwd)

{

try (

// Open a connection

Connection conn = DriverManager.getConnection(

"jdbc:oracle:thin:@db.yale.edu:1521:univdb",

userid, passwd);

// Create a statement object

Statement stmt = conn.createStatement();

) {

try {

// Execute queries using the statement object

stmt.executeUpdate(

"insert into instructor values(’77987’,’Kim’,’Physics’,98000)");

}

catch (SQLException sqle) {

System.out.println("Could not insert tuple. " + sqle);

}

// Execute queries using the statement object

ResultSet rset = stmt.executeQuery(

"select dept_name, avg (salary) "+

" from instructor "+

" group by dept_name");

while (rset.next()) {

System.out.println(rset.getString("dept_name") + " " +

rset.getFloat(2));

}

}

catch (Exception sqle) {

// handle exception

System.out.println("Exception : " + sqle);

}

}

Automatic Commit. Most DBs treats each SQL statement as a transaction by default.

To create a transaction, automatic commit must be turn off.

assert conn instanceof Connection;

conn.setAutoCommit(false);

A transaction can be put between

conn.commit();

stmt.executeUpdate(...);

conn.rollback();

Savepoints And Nested Transactions

The examples above are flat transactions.

A flat transaction typically refers to a transaction that doesn’t involve multiple steps or subtransactions. It’s a simple, single-operation transaction where a database operation is executed as a single unit of work.

A typical flat transaction:

BEGIN WORK

S1: book flight from Melbourne to Singapore

S2: book flight from Singapore to London

S3: book flight from London to Dublin

COMMIT WORK

The semantic of flat transaction is “all-or-nothing”

- A naïve implementation: giving up everything that has been done (invoke

ROLLBACK WORK) - Good at short applications such as debit/credit

- Problem: waste of computation power

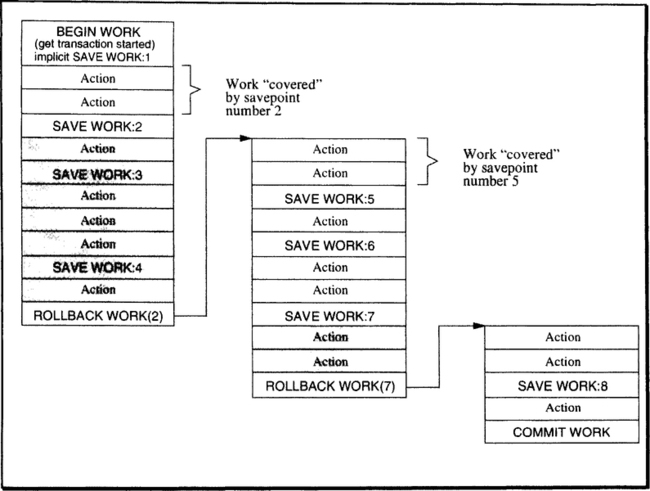

A better solution: stepping back to an earlier state inside the same transaction by savepoints

Savepoints are explicitly established by the application program and can be reestablished by invoking a modified ROLLBACK function, which is aimed at an internal savepoint rather than at the beginning of the transaction.

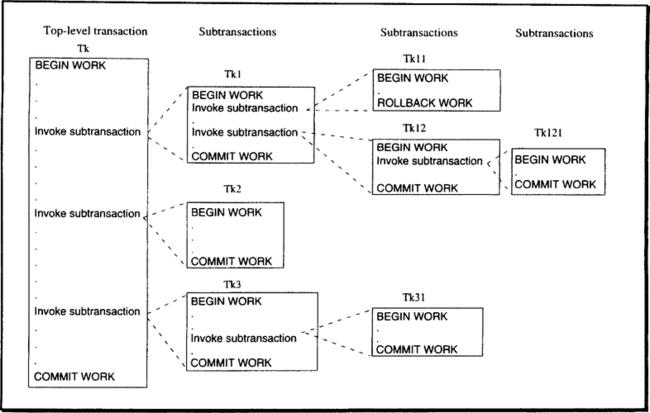

An alternative to savepoints is nested transactions (or subtransactions)

Nested transactions are a generalization of savepoints. Whereas savepoints allow organizing a transaction into a sequence of actions that can be rolled back individually, nested transactions form a hierarchy of pieces of work.

Definition of nested Transaction:

- A nested transaction is a tree of transactions, the sub-trees of which are either nested or flat transactions.

- A subtransaction can either commit or roll back; its commit will not take effect, though, unless the parent transaction commits. By induction, therefore, any subtransaction can finally commit only if the root transaction commits.

Rules of subtransactions:

- Commit rule. The commit of a subtransaction makes its results accessible only to the parent transaction. Any subtransaction can finally commit only if the root transaction commits.

- Rollback rule. If a transaction at any level is rolled back, all its subtransactions are also rolled back

- Visibility rule. All changes done by a subtransaction become visible to the parent transaction upon the subtransaction’s commit. All objects held by a parent transaction can be made accessible to its subtransactions. Changes made by a subtransaction are not visible to its siblings, in case they execute concurrently. Siblings cannot view each other.

subtransactions are more capable than savepoints + flat transaction:

- subtransactions can run in parallel so more effecient.

- the code will be more organizable

Conclusion: subtransactions have ACI, but no D (The changes are made durable only after the whole transaction has committed)

Transaction Processing Monitors

TP monitors are the least well-defined software term. They function differently in different DBMS.

The main function of a TP monitor is to integrate other system components and manage resources.

The TP monitor integrates different system components to provide a uniform applications and operations interface with the same failure semantics (ACID properties).

In this subject, TP monitors are defined to be

- TP monitors manage the transfer of data between clients and servers

- Breaks down applications or code into transactions and ensures that all the database(s) are updated properly

- It also takes appropriate actions if any error occurs

Services:

- Terminal(clients) management. manage connections, deliver and receive message by users

- Presentation services. dealt with different UI software, similar to the previous one

- Context management. context such as “Current authenticated userid at that terminal,” “Default terminal for that user,” “Account number for that user,” “Current user role.”…

- Start/restart. handle the restart after any failure

Structures of TP Monitors

One process per terminal

Each process can run all applications. Each process may have to access any one of the databases. This design is typical of time-sharing systems. It has many processes and many control blocks.

Very memory expensive, context switching causes problems too..

Only one terminal process

In this solution, there is just one process in the entire system. It talks to all terminals, does presentation handling, receives the requests, contains the code for all services of all applications, can access any database, and creates dynamic threads to multiplex itself among the incoming request

This would work under a multithreaded environment but cannot do proper parallel processing, one error leads to large scale problems, not really distributed and rather monolithic

Many Servers, One Scheduler

Multiple processes have one requester, which is the process handling the communication with the clients.

Multiple communication processes and servers

Generalization of the coexistence approach: multiple application servers invoked by multiple requesters. The association between these groups of functionally distinct processes, load control, activation/deactivation of processes, and so on, must now be coordinated by a separate instance, the monitor process.

Transaction Concurrency Control

Concurrency control guarantee the isolation properties

Idea: impose exclusive access to shared variables on different threads.

Approaches:

- Dekker’s Algorithm – needs almost no hardware support. but high complexity

- OS support primitives – simple to use, expensive, dependent on OS

- Spin locks – the most common mechanism in DBMS Atomic lock/unlock instructions

Dekker’s Algorithm

int turn = 0 ; int wants[2]; // both should be initially 0

…

while (true) {

wants[i] = true; // claim desire

while (wants[j]) {

if (turn == j) {

wants[i] = false;

while (turn == j);

wants[i] = true;

}

}

counter = counter + 1: // resource we want mutex on

turn = j; // assign turn

wants[i] = false;

}…

- Manage desire by arrays

- Use loop statement to wait (busy waiting) → waste of computation power

- Transfer turn to others when task is done

OS Exclusive Access

OS support primitives as lock and unlock

- Do not use busy waiting, but also very expensive

- also OS dependent

Spin Locks

- Executed using atomic machine instructions such as test and set or swap

- Need hardware support ← need to lock bus

- uses busy waiting

- very efficient for low lock contentions, commonly used in DBMS

int lock = 1;

// lock granted

acquire(lock);

while(!testAndSet(&lock)); // busy waiting

counter = counter + 1

// release lock

lock = 1;

testAndSet(int* lock) {

// Assume this line runs in atomic

if(*lock == 1) {*lock = 0; return true} else {return false}

}

Yet another spin lock – compare and swap

more generic lock mechanism in programming languages:

lock(var);

unlock(var);

Semaphore

Definition: A bit, token, fragment of code, or some other mechanism which is used to restrict access to a shared function or device to a single process at a time, or to synchronize and coordinate events in different processes.

Semaphores derive from the trains: a train may proceed through a section of track only if there is no other train on the track. Else, it waits

Implement in computers:

- A general

getsubroutine to acquire access, and agiveto give access to others - Put waiting processes into a queue to let them wait (simplest: a linked list)

- After a process release the access, give it to the very next process

Semaphores are simple locks; no deadlock detection, no conversion, no escalation…

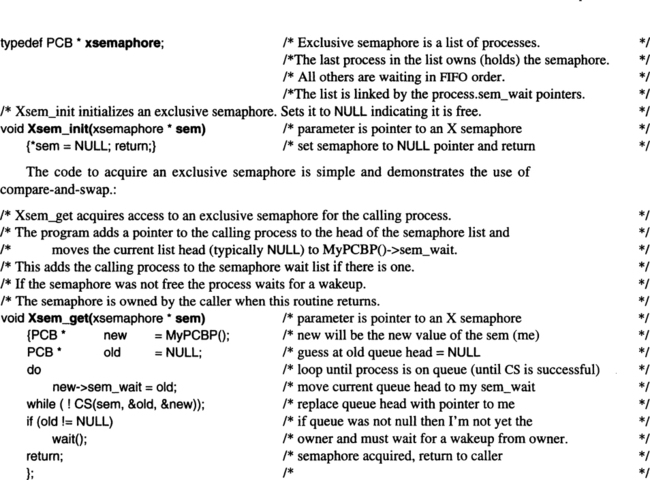

Exclusive Semaphores. An exclusive semaphore is a pointer to a linked list of processes, indicating the exclusive ownership of resources. The process at the end of the list own the semaphore.

To acquire a semaphore, a process needs to call get()

An example get() of an exclusive semaphore

Note that CS stands for “compare-and-swap“ (a spin lock)

boolean cs(int *cell, int *old, int *new)

{/* the following is executed atomically*/

if (*cell == *old) { *cell = *new; return TRUE;}

else { *old = *cell; return FALSE;}

}

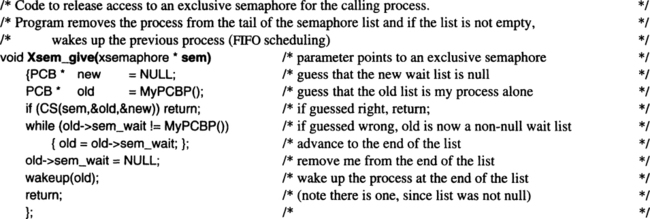

After finishing all things, a process call give() to wake up the first process in the waiting list

An example give() of an exclusive semaphore

Problem of Exclusive Semaphore: Dead Locks

Solution to dead locks:

- Have enough resources – not practical

- don’t allow a process to wait permanently. simply rollback after a certain time bad idea too. causing resources waste and repeated deadlocks. it causes live locks → constantly change the state of processes but with no actual progress

- Linearly order the resources and request of resources should follow this order – practical guarantees that no cyclic dependencies among the transactions. i.e. a transaction after requesting ith resource can request jth resource if j > i. it applies to statis resources such as printers, but it generally can’t apply to db in general because you don’t know how to order things until runtime

- pre-declare all necessary resources and allocate at once

- Periodically check cycles in graphs

if a cycle exists, rollback one or more transaction

not common in practical:

- check if there is a cycle in distributed states is impossible to be absolutely correct

- how to decide which transaction to sacrifice?

- Allow waiting for a maximum time on a lock then force Rollback: Many successful systems (IBM, etc) have chosen this approach…

- Most practical approach: allow a transaction waiting for a maximum time on a lock then force rollback

Concurrency Control For Isolation

The relation between concurrency control and isolation can be described in two aspects:

- Concurrent transaction leaves the database in the same state as if the transactions were executed separately

- Isolation guarantees consistency, provided each transaction itself is consistent No inconsistency arise from allowing concurrency

By the way, why not just achieve isolation by sequentially processing each transaction? Because efficiency is also important in DBMS.

Therefore, we need to use concurrency control to support properties of concurrent transactions:

- concurrent execution should not cause programs to malfunction

- concurrent execution should have higher throughput (otherwise abandon it)

Achieve Concurrency Control in DB

The tool: dependency graphs

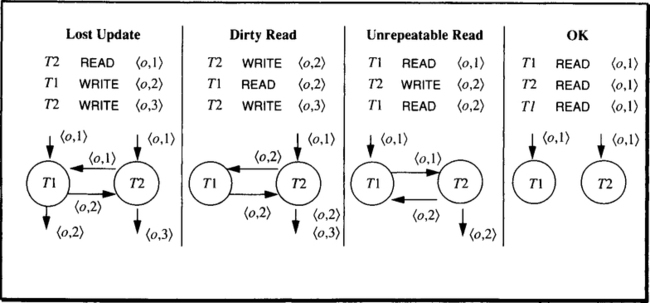

The dependencies induced by history fragments. Each graph shows the two transaction nodes T1 and T2 and the arcs labeled with the object 〈name,version〉 pairs.

A simple observation: read doesn’t cause concurrency issue

Possible Issues:

- Lost Update: Write after write

- Dirty Read: Read after write

- Unrepeatable Read: READ→WRITE→READ